The next big thing in mechanical keyboards is magnetic switches.

Mechanical keyboards quickly went from a niche product to mainstream during the pandemic, as everybody was looking to upgrade their home offices — and maybe for a new hobby, too. Brands like Akko, Drop, Ducky, Epomaker and Keychron became household names and today’s enthusiasts can choose between dozens of different layouts and buy parts from even more vendors.

Since then, things have gotten a bit stale — even as what were once high-end features have migrated to budget keyboards. RGB lighting has long become standard, as the likes of Angry Miao and others continue to find innovative new ways to use it. The number of switches available feels infinite, from the lightest switches for gamers to the heaviest for even the most energetic typist — all in linear, tactile and clicky variants and an endless amount of colors. A few years ago, a gasket-mounted keyboard, which gives you a softer, bouncier typing feel, was something enthusiasts could only find on high-end boards, but now everybody essentially does the same.

In some ways, that’s great: the average build quality of mechanical keyboards on the market has never been higher and prices have come down. But the entire scene has also become a little bit boring. That’s where magnetic switches, with their ability to quickly change the actuation point (the point during the keypress where the switch registers your downstroke), come in.

Image Credits: Akko

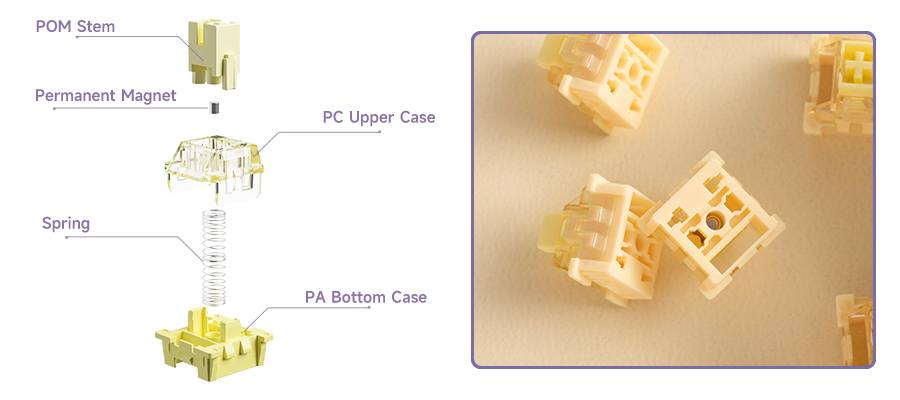

On a standard mechanical keyboard switch, you physically close an electrical circuit to register a key press. When you push down, the two legs on the stem (the moving part the keycap is attached to) push against two metal leaves that close the circuit.

The shape of that stem and its legs are what actually differentiates a linear switch (think Gateron Red switches on many gaming keyboards) from one that has a more tactile feel (like on a Cherry Brown). Linear switches have smooth stems while there is a bump on tactile switches that provide that slight moment of resistance as you press down. The overall design of the stem, its legs, the spring, the stem sits on and the overall switch housing can drastically change how a switch feels and sounds — but also when exactly the keypress is registered by the keyboard. For a standard Gateron Red, for example, the actual keypress is registered after you press down about 2 millimeters and the overall travel distance before the stem hits the bottom of the switch is 4 millimeters.

Mechanical switches are very different. They rely on magnets and springs and activate by sensing changes in the magnetic field. Popularized by Dutch keyboard startup Wooting, these switches rely on the Hall Effect and have actually been around since the 1960s. They still use the same overall design as mechanical switches, with stems and springs, but since there’s no electrical circuit to close, there are no legs on the stem. There is, however, a permanent magnet in the stem and as you press down, the sensor on the keyboard’s PCB precisely registers what position the switch is. And that’s where the most important change comes in: you can change how far you need to press down to register the keystroke.

Akko’s

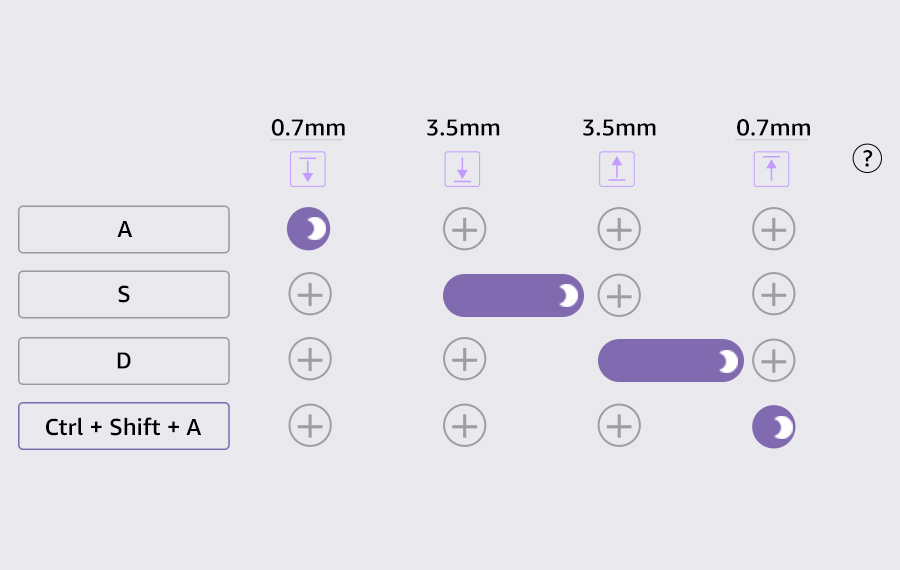

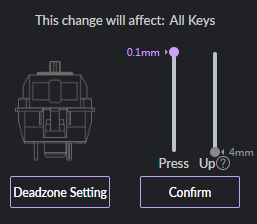

When you’re gaming, you may want to register it the moment you start moving your finger 0.1 millimeter, but then when you are using the same keyboard to type, you can change that to, say, 2.5 millimeter to avoid errant keystrokes. Typically, that’s done with a simple key combo on the keyboard itself or in the manufacturer’s software tools. Because these sensors are sensitive to temperature variations, there’s also typically an option to calibrate the keyboard.

This also allows for a few other smart tricks because you can’t just change where the keypress is triggered but also where it is released. That’s not likely to matter too much to you as you type, but when gaming, that’s what allows you to quickly spam a key as needed (and most tools that come with magnetic keyboards also have a rapid trigger setting), all while this high degree of customization allows you to experiment with your favorite settings without having to physically change to a different switch.

Image Credits: Akko

If you want to go overboard, you can even create something akin to a macro by assigning multiple actions to the same key, so that a single keypress registers a different action when you’ve pressed half-way down, as you bottom out and when the switch pushes the keycap up again — and maybe another one somewhere in-between. I haven’t quite found a personal use case for this yet, but somebody surely will.

The one thing you can’t change, though, is the switch’s resistance. Despite all of the talk of magnets, that’s still handled by the spring inside the switch, after all.

One problem here is that there still isn’t quite a standard for these switches, so not every switch is going to work on every keyboard. Depending on the manufacturer, however, you may be able to plug in traditional mechanical switches into the PCB, too (though without the customization benefits of the magnetic switches, of course).

A trip to Santorini: Akko’s MOD 007B PC

To test all of this out, Akko sent me a review unit of its MOD007B PC Santorini keyboard – one of the latest in its World Tour series and also one of the more restraint designs in that series. Priced at just under $150 (though you can usually get it for around $110 on Amazon), the gasket-mount MOD007B PC comes pre-built with Kailh’s linear Sakura Pink magnetic switches. The PCB also accepts 3-pin mechanical switches.

For connectivity, you get the standard Bluetooth and USB-C connections, as well as a multi-host 2.4Ghz option (which requires the included dongle). For wireless operations, the board is powered by a 3600mAh battery.

Image Credits: Frederic Lardinois/TechCrunch

The 75-percent case isn’t anything too exciting, with its rather plain polycarbonate case, but unlike even some high-end keyboards, it allows you to adjust your typing angle with the help of its dual-position feet.

Akko used a nice amount of foam inside the case to shape the board’s sound, which is on the clacky side. I prefer a slightly more dampened sound, but that’s 100% a personal preference. The stabilizers are nicely tuned, but there is a noticeable amount of case ping. A few small mods should take care of that, but out of the box, that’s the most obvious negative of this board and I’m surprised that after multiple generations of MOD007 boards, the company hasn’t fixed that. A few small modifications should take care of that, but even at this price point, buyers shouldn’t have to do that.

As for the software, Akko’s own proprietary software tool is competent and easy enough to use. It does what it’s supposed to do and gets out of your way. That’s one thing about board with magnetic switches: they tend to favor proprietary software over open-source solutions like VIA.

Image Credits: Akko

This board is all about the magnetic switches, though. I enjoyed experimenting with them quite a bit and even if I didn’t win a single chicken dinner in PUBG will testing it, I did get the sense that at the right setting, it allowed me to react just a little bit faster. Your mileage may vary in Valorant and other shooters where the rapid trigger functions may be more important. Either way, though, it’s a fun board to game with.

The switch is a Khailh Sakura Pink magnetic switch with a 50gf bottom-out force. That’s in line with many standard linear switches, though maybe a bit on the heavier side.

For day-to-day typing, it took me a while to find the right setting. I experimented with a few, but in the end, I ended up with Akko’s default comfort setting, which sets the actuation and release points at 2mm. The default gaming setting is 0.5mm, which seems more than fast enough.

While not the most premium board on the market, Akko has created a board that, with the right settings and a few minor mods, is pleasant to type on (if you like linear switches) and makes for a nice gaming platform, too. What matters most here, though, is that this board allows gamers and non-gamers alike to dip their feet into the magnetic switch market without a major upcharge. Is it the best board out there? Not by a mile — but at this price point, it’s hard to beat.

techcrunch.com